With the impending release of Disney’s live-action remake of The Little Mermaid, let’s dive into the fascinating history of this cryptozoological creature.

1. The first-ever recorded merbeing used he/him/his

c. 2300 BC (design); 2012 (this file), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In the realm of ancient mythology, a mythical creature emerges as a captivating embodiment of the enigmatic ocean—the first merbeing, Assyrian-Babylonian sea-god Ea, also known as Enki to the Sumerians. Picture a majestic being, adorned with the ethereal fusion of a human torso and a fish’s tail, gracefully rising from the depths of the Persian Gulf. Ea, a figure of immense allure, seamlessly connected the terrestrial and aquatic realms, captivating all with his profound wisdom and mystical charm.

The mesmerizing tales of Ea transcend the boundaries of a single civilization, resonating across ancient cultures. The Greeks, captivated by his timeless elegance, identified him as Oannes—a captivating entity that shared Ea’s aquatic grandeur, imparting humanity with profound knowledge and enlightenment. The merging of these narratives represents the profound interconnectedness of diverse cultures as their mythologies intermingled and evolved.

However, Oannes, although often depicted as a fish-like being, should not be considered the first mermaid in the traditional sense. While Oannes emerged from the sea and possessed fish-like qualities, the concept of mermaids as we commonly understand them—half-human and half-fish—predates the figure of Oannes.

2. Atargatis (Astargatis) the first-ever recorder mermaid, plunged herself into a lake because of unbearable sorrow

Atargatis, also known as Astargatis, was worshipped in various ancient Near Eastern civilizations from approximately the 3rd century BCE until the 4th century CE. Her worship primarily flourished among the Assyrians, Babylonians, Phoenicians, and other cultures of the region.

One of the most captivating and enduring tales surrounding Atargatis revolves around her transformation, a story that has fascinated ancient Near Eastern cultures for centuries. According to myth and legend, Atargatis, overcome by grief and despair, sought solace and release by plunging into the depths of a sacred lake.

The precise reasons for Atargatis’ sorrow vary across different mythological interpretations and accounts. However, one commonly cited cause of her sadness is often associated with a tragic event involving her son or lover, depending on the specific mythological version.

In some versions of the myth, Atargatis’ son or lover—often named Melqart or Ichthys—meets an untimely demise. The circumstances surrounding this event differ, ranging from accidental deaths to battles with mythical creatures. Regardless of the details, the loss of her loved one plunges Atargatis into deep grief and despair, leading her to seek solace or escape by immersing herself in the sacred waters.

Emerging from the depths of the lake, Atargatis reemerged with a lower body resembling that of a fish and an upper body maintaining her ethereal human form. This extraordinary transformation represented her enduring presence in both the watery realms and the world of humans. As a mermaid-like being, Atargatis became a symbol of duality—a bridge between two realms, embodying the power and mystery of the underwater world while retaining her connection to humanity.

This profound transformation elevated Atargatis to a divine status associated with water, fertility, and protection. She became a revered figure, worshipped in sanctuaries and temples throughout the ancient Near East. Devotees sought her blessings, particularly in matters of fertility and the bountiful abundance of aquatic resources. Atargatis’ image adorned sacred spaces, where her presence and influence were invoked through offerings, rituals, and prayers. The captivating tale of her transformation resonated with people, serving as a reminder of the deep mysteries and connections between humanity and the watery realms that surround us.

The earliest evidence of Atargatis’ worship can be traced back to the Hellenistic period when the Greek influence in the Near East began to merge with existing local traditions. During this time, the worship of Atargatis gained popularity and spread to different regions.

Atargatis, a revered goddess of ancient Near Eastern civilizations, was associated with water, fertility, and protection. According to mythology, she was born from the union of the sky god Uranus and the earth goddess Gaia. As a deity with fish-like attributes, Atargatis was believed to have emerged from the sacred waters, symbolizing her connection to the life-giving power of rivers, lakes, and the sea. She was venerated as a mother goddess, associated with maternal love and protection.

While both deities were associated with water, fertility, and had connections to aquatic life, Enki’s origins predate the worship of Astargatis by several millennia. Enki’s worship and mythology had a profound influence on subsequent Mesopotamian cultures, including the Assyrians and Babylonians, who incorporated aspects of Enki into their own religious traditions.

3. The stories of mermaids probably weren’t started by horny seamen

The origin and development of mermaid legends cannot be solely attributed to the imagination of “horny sailors.” While it is true that sailors’ encounters with marine creatures and their isolation at sea may have contributed to the folklore surrounding mermaids, the concept of mermaids predates the seafaring traditions.

Mythical creatures resembling mermaids can be found in various cultures throughout history, such as the ancient Assyrians, Babylonians, and Greeks, who depicted half-human, half-fish beings in their folklore. These stories emerged from a complex interplay of cultural, religious, and symbolic elements. Mermaids were often associated with the sea, embodying both its beauty and treacherous nature.

Furthermore, mermaid legends are not solely tied to sailors’ tales but also have deep roots in ancient mythologies, where they represented concepts like transformation, fertility, and the connection between humans and the natural world. These mythical creatures captured the human imagination, transcending the realms of folklore and becoming enduring symbols in art, literature, and popular culture.

While there may be accounts of sailors mistaking manatees or seals for mermaids, it is important to recognize that mermaid lore goes far beyond these isolated encounters. The fascination with mermaids and their existence in various cultural narratives points to a deeper human longing for the mystical, the unknown, and the enchantment of the sea.

4. Sirens in The Odyssey weren’t mermaids

While both sirens and mermaids are mythical creatures associated with the sea, they are distinct entities with different characteristics and appearances. In the context of Homer’s epic poem, “The Odyssey,” the creatures encountered by Odysseus are referred to as sirens, not mermaids.

In “The Odyssey,” the sirens are depicted as enchanting and dangerous beings who lure sailors with their captivating songs. Their voices possess an irresistible allure, drawing unsuspecting sailors towards them, often resulting in shipwrecks and destruction. The sirens’ goal is to entice and ultimately devour the sailors who succumb to their enchanting melodies.

Mermaids, on the other hand, are typically depicted as half-woman, half-fish creatures. They possess the upper body of a human and the lower body of a fish. Mermaids are often associated with beauty, grace, and mystery. They are known for their mesmerizing singing voices and are often portrayed as benevolent beings or guardians of the sea.

In “The Odyssey,” Homer does not describe the sirens as having fish-like tails, which is a distinguishing characteristic of mermaids. Therefore, while both sirens and mermaids are alluring creatures associated with the sea, the specific beings encountered by Odysseus in “The Odyssey” are referred to as sirens, not mermaids.

5. Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid was a gay allegory

We’ve seen the comparisons between Disney’s beloved classic The Little Mermaid (1989) and its original source material, the dark and violent tale of the same name, written by Hans Christian Andersen.

To be fair, classic Disney has had a long history of butchering fairy tales and serving them as some kind of cheerful, less gory and rapey Frankenstein monsters, which is a really smart move in some (Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Beauty & the Beast) while problematic in others (Pocahontas, Pocahontas 2, Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Hercules).

The original The Little Mermaid that came out in 1989 kind of falls in the middle. It offers a nice package in a gorgeous bow (although, what’s wrong with the name “Mildred?”) and yet it robs our hero of her own agency and arc.

Whilst Ariel’s (the Disney 1989 version) longing to be a human is rooted in her curiosity and suspicion that humans aren’t all bad (and is later strengthened because she falls in love with Prince Eric), our nameless mermaid in Andersen’s tale yearns to be human so she can have an immortal soul.

“If men aren’t drowned,” the little mermaid asked, “do they live on forever? Don’t they die, as we do down here in the sea?”

“Yes,” the old lady said, “they too must die, and their lifetimes are even shorter than ours. We can live to be three hundred years old, but when we perish we turn into mere foam on the sea, and haven’t even a grave down here among our dear ones. We have no immortal soul, no life hereafter. We are like the green seaweed – once cut down, it never grows again. Human beings, on the contrary, have a soul which lives forever, long after their bodies have turned to clay. It rises through thin air, up to the shining stars. Just as we rise through the water to see the lands on earth, so men rise up to beautiful places unknown, which we shall never see.”

“Why weren’t we given an immortal soul?” the little mermaid sadly asked. “I would gladly give up my three hundred years if I could be a human being only for a day, and later share in that heavenly realm.”

The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen

But there’s an even deeper yearning in the tale.

Andersen wrote The Little Mermaid as an allegory to cope with his own loss when the object of his erotic love, Edvard Collin, the son of Andersen’s benefactor and official guardian Jonas Collin.

Wilhelm Marstrand, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Details are murky about whether the younger Collin had sex with Andersen. However, when Collin announced he was marrying a woman, Andersen seemed to have snapped, moved away, and wrote the tale.

In letters written to his beloved young friend Edvard Collin in 1835–6 Andersen said “Our friendship is like ‘The Mysteries’, it should not be analyzed,” and “I long for you as though you were a beautiful Calabrian girl.”

Rictor Norton

Then, Edvard announced his plans to get married—to a woman. Andersen was devastated. But he kept smilingly inserting himself, even sending letters to the young Collin’s fiancé, Henriette. Soon, this façade crumbled, and he appeared to be trying to stop the marriage from happening altogether. When Edvard, in a less angered moment, defined Andersen as a “worthy friend” in a letter in 1836—the year of his wedding—Andersen finally seemed to snap. From the island of Fyn, where he had retreated, he wrote a sharp, subtly erotic rebuke to his unavailable crush:

Why do you call me your “worthy friend?” I don’t want to be worthy! That is the most insipid, boring word you could use. Any fool can be called worthy!…. I have hotter blood than you and half of Copenhagen. Edvard, I feel so infuriated by this loathsome weather! I also long for you, to shake you, to see your hysterical laughter, to be able to walk away, insulted, and not come back home to you for two whole days.

Dear Internet: The Little Mermaid Also Happens to Be Queer Allegory by Gabrielle Bellot

By writing this post, I’m not trying to say I wish The Little Mermaid had a gay character. I mean, I wish they did because it’d be fun?

However, I’ve seen how adding a queer character could work very well (Star Trek: Discovery, main characters; Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, supporting characters), work just okay (Lightyear, supporting characters), to just feel so half-baked (Star Trek Beyond, extra; Watchmen, extra) or feel super forced (Strange World, main character).

I was born in the eighties in Indonesia. Granted, I was raised in a cosmopolitan city (Jakarta) and had a sheltered life with parents who knew I was gay since I was a kid, and they were okay with it. But when I went to an all-boy Catholic school, I didn’t proclaim my crushes to my classmates. Actually, my best friend did that and it became a tumultuous first year. I felt that longing, that yearning, that pain of unrequited love. And I felt it quite often, sometimes exacerbated by holding in the secret of crushing on someone even when everyone knew I was gay.

Even after falling in love with the classic Disney version of The Little Mermaid, the morbid side of me could appreciate the devastating sacrifice and the justifiably deserved happy ending of Andersen’s The Little Mermaid.

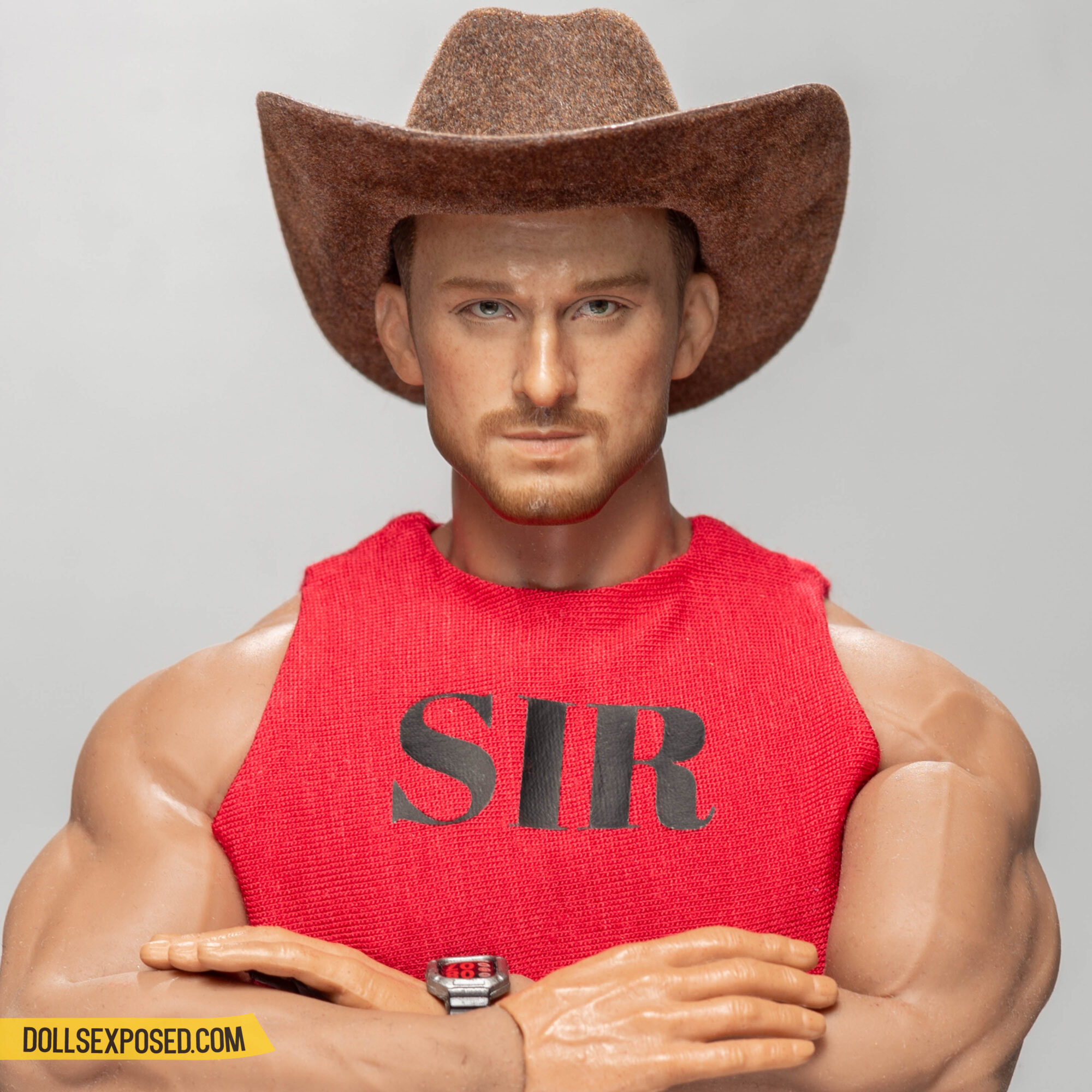

So, to celebrate MerMay (I’m so late, I know), I’m doing a tribute to both Sade’s “No Ordinary Love” music video with Matt as The Sailor and Chrissy as the mermaid) while our resident Disney freak Wade dresses up as the dashing Prince Eric from the Disney classic animation.

BTS Thoughts:

Par for the course, I’ve had these fake aquarium plants for years. My modus operandi is always about buying all the stuff I need to do a shoot and then delaying the actual shoot partly because I’m lazy, partly because I don’t have time or can’t make time, and partly because I’m terrified the end result won’t be as spectacular as my imagination.

But there’s no reason to delay anymore.

The seabed is actually a tablecloth with a refracted sunlight print. Gayriel’s (Chrissy’s merfag name) cove is a fake sunning rock for lizards.

I can proudly say I made Gayriel’s tail, unfortunately, sometimes it doesn’t translate too well on camera as the sequins appear completely white and lose their pearlescence. I also wish I’d sewn some kind of wiring in the fins so they wouldn’t be all too flippity-flap.

And yes, instead of a bridal magazine that Sade reads in the iconic No Ordinary Love video, Gayriel’s reading a copy of Physique Pictorial. Quite possibly the very reason why he’s interested in going to the surface.

The question is, how does a magazine survive underwater? Also, what are the boys and Thor going to do to Gayriel?

Hey, you gorgeous thing!

Keeping this space sizzling for free isn’t easy (think: hosting costs, doll accessories, and lube—lots and lots of lube).

But we realized it’s almost impossible to keep going without your help. And we get it—times are tough, so any support you can offer means the world.

If we’ve made you horny, laugh, cum, or feel something special, why not give a little love back? 💖

Every donation keeps the smut (and culture) going—and trust us, at this point in our lives, we’re so grateful we’re able to produce this content regularly.

Thanks. You’re a doll. 😘

Dollsexposed showcases homoerotica and kink through twelve-inch doll photography. Their adventures in the doll world began in 2011 before establishing a home on dollsexposed.com eleven years later.

Dollsexposed's works have been displayed at the Seattle Erotic Art Festival, Los Angeles Kinky Art Show, and Los Angeles Leather Getaway.

If you enjoy this site, please consider tipping to keep the website afloat.

you may also enjoy:

Boys for All Seasons

An interview with Dollsexposed’s two most eligible bachelors, business owners, and best friends. Shot on location in Malibu.

A Different Kind of Valentine

How Matt and Chrissy spend their Valentine’s Day this year, inspired by the visual language of 1959’s “Pillow Talk.”

A Day in the Life of WadeSoftcore

Wade’s daily routine keeps him sane, but at night, he’s distracted by memories of meeting Chrissy and Matt for the first time.

A Potluck Dinner

A synagogue social event forces Wade to confront grief, responsibility, and the parts of his life he’s been trying not to touch.

Matt’s Aftermath

It’s been six months since Chrissy left Matt. Is he ready to move on? Should he even be thinking about it?

A Room of One’s OwnNudity

After moving out of the apartment he shared with Matt and losing almost all of his safety nets, Chrissy has to fend for himself.